scinerds:

lagos2bahia:

atane:

dynamicafrica:

Toda...

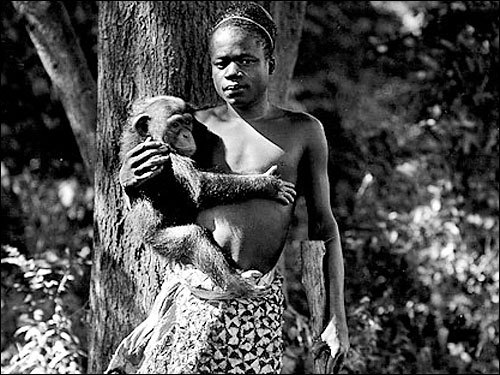

Today, March 20th, marks the suicide death of Ota Benga.

On this day in 1916, after years of dehumanization and depression, Benga committed suicide by shooting himself in the heart with a stolen pistol.

He was 32.

The Tragic Story of the Life of Ota Benga

Born in Congo in 1883, Ota Benga - a Congolese “pygmy” of the Mbuti tribe - lived a short life that was both troubled and tragic. Benga lived a peaceful and fairly normal existence in the forests of Congo, near the Kasai River, until his people were horribly and brutally slaughtered by King Leopold’s armed forces known as the Force Republique. It was during this massacre that Benga lost his wife and children, and only survived as he was out hunting. Upon his return to his village, he was captured by the very people that had killed his family and tribespeople and subsequently sold into slavery.

Whilst at a slave market, Ota Benga caught the eye of Samuel Phillips Verner - an American missionary and businessman that was in Africa scouting for pygmies to perform in an exhibition at the St Louis World Fair, on behalf of the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition and as part of an anthropological display that would feature “representatives of all the world’s peoples”.

For “a pound of salt and a bolt of cloth”, Verner purchased Benga and the two developed a sturdy bond as Benga regarded Verner as his saviour from slavery. Ota Benga, along with a group of other men from local Congolese tribes, made their way to St. Louis, sans Verner who fell ill with malaria, where they were put on display at the World Fair.

This is next paragraph is an excerpt from Ota Beng’a wikipedia page:

“When Verner arrived a month later, he realized the pygmies were more prisoners than performers. Attempts to congregate peacefully in the forest on Sundays were thwarted by the crowds’ fascination with them, as were attempts to present a “serious” scientific exhibit. On a July 28, an attempt to play to the crowd’s preconceived notion that they were “savages” resulted in the First Illinois Regiment being called in to control the mob. Benga and the other Africans eventually performed in a military-style fashion, imitating that of the Indians at the Exhibition. The Indian chief Geronimo (himself on display as “The Human Tyger” – with special dispensation from the Department of War) came to admire Benga and gave him one of Geronimo’s famed arrowheads. For his efforts, Verner was awarded the gold medal in anthropology at the Exposition’s close.”

After the Exposition, Benga returned to his home country where he accompanied Verner on his further expeditions in Africa. Benga got married for a second time to a woman from Batwa tribe but unfortunately, he once again lost his partner - this time, to a snake bite. As Verner prepared to go back the US, Benga decided to leave Congo once again with his trusted American friend. Sadly, this decision would lead to further degradation under the guise of “Anthropological Research”, as he was housed in a room at the American Museum of Natural History, where he was occasionally paraded around in a duck costume to entertain visitors.

According to the biography on Ota Benga written by Bradford and Blume, Ota Benga was enchanted with the museum at first. However, as time passed, he sunk into a state of depression as he became more and more homesick, which lead Benga to act in several ways. Once, he tried to make his escape from the museum by leaving as a large crowd was exiting.

“What at first held his attention now made him want to flee. It was maddening to be inside – to be swallowed whole – so long. He had an image of himself, stuffed, behind glass, but somehow still alive, crouching over a fake campfire, feeding meat to a lifeless child. Museum silence became a source of torment, a kind of noise; he needed birdsong, breezes, trees.”Bradford and Blume (1992), pp. 165-166

After the failed attempt at housing Ota Benga at the National History Musuem, Verner soon found another home for him at the Bronx Zoo. Here, Benga was given free roam of the premises and soon found a friend in an oranguatan name Dohan, who lived in the Monkey House. Noticing this, the Zoo director, William Hornaday, took of advantage of this friendship and it wasn’t long before Benga was living in the Monkey House and became part of the exhibit with the oranguatan. Furthermore, Madison Grant - a eugenicist and scientific racist at that time - encouraged the exploitation of Benga in this exhibition at the Zoo, and used it to promote theories and beliefs such as Darwinism and racial supremacy. In fact, the New York Times had this to say about Benga’s display at the zoo:

“We do not quite understand all the emotion which others are expressing in the matter … It is absurd to make moan over the imagined humiliation and degradation Benga is suffering. The pygmies … are very low in the human scale, and the suggestion that Benga should be in a school instead of a cage ignores the high probability that school would be a place … from which he could draw no advantage whatever. The idea that men are all much alike except as they have had or lacked opportunities for getting an education out of books is now far out of date.”

It wasn’t long until this exploitative display was met with controversy. African-American groups protested the degridation of Ota Benga, and as a result, he was once again given free roam of the zoo. This time, however, the zoo promoted Benga as a sort of “interactive exhibit”, and as he walked around, he was frequently taunted and harassed, both physically and verbally, by visitors at the zoo. In frustration, Benga began to act out vehemently. Once again, The New York Times had something to say concerning Ota’s abuse at the zoo. Unlike the earlier statement, The NYT exchanged hostility for humanity in saying,

“It is too bad that there is not some society like the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. We send our missionaries to Africa to Christianize the people, and then we bring one here to brutalize him.”

With mounting public pressure, the zoo eventually caved to public pressure and Benga was removed and was later housed at the Howard Colored Orphan Asylum. Despite the move, the attention that he loathed at the zoo haunted him once again: this time, through the press. Ota Benga was then relocated to Lynchburg, Virgina, where he was tutored by poet Anne Spencer and soon began a formal education. His teeth, which were previously shaven in a sharp, triangular formation during the days of his youth, were capped and he was dressed in Western fashions of the time. With the improvement of his English skills, Benga left school and began working at a tobacco factory, and also began planning his trip back to Congo. Sadly, with the outbreak of World War I, his hopes were soon dashed. Benga became overwhelmed with depression and on March 20, 1916, at the young age of 32, “he built a ceremonnial fire, chipped off the caps of his teeth and shot himself in the heart with a stolen pistol.”

Excerpts from wikipedia regarding Ota Benga’s burial and legacy:

“He was buried in an unmarked grave, records show, in the black section of the Old City Cemetery, near his benefactor, Gregory Hayes. At some point, however, both went missing. Local oral history indicates that Hayes and Ota Benga were eventually moved from the Old Cemetery to White Rock Cemetery, a burial ground that fell into disrepair.

Phillips Verner Bradford, the grandson of Samuel Phillips Verner, authored a 1992 book on Ota Benga entitled Ota Benga: The Pygmy in the Zoo. During his research for the book, he visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York, which holds a life mask and body cast of Ota Benga. To this day, the display is still labeled “Pygmy”, rather than indicating Benga’s name, despite objections that began almost a century ago from Verner himself.”

(via )

(via )

One single facet, of an endless multitudes of cruelty and callousness, racism and inhumanity. To make themselves human, they had to dehumanize the world, and on hierarchy no less. Rethink your museums, your institutions, your ignorance. What else is hiding from your conscience, right below the surface? What do museums stand for, symbolize?

(via )

(via )

Be nice. Do work. Amazing things will happen.